|

REQUIREMENTSFor this “big paper,” you need to…

STEP 1: Getting organized Gather all your materials:

Now put anything you’ve written related to your topic into one place / document in Google Drive or your new OneDrive.com. STEP 2: Down Draft One way to get started writing something as daunting as this essay is to write in pieces. So instead, take one point at a time. This is a time to just get things down (hence, the idea of the “down draft,” a concept I first learned about from teacher Kelly Gallagher). You can go back later to organize and revise.

Write a “graff-like” templateNext, find a source in your anthology to answer that question. Write 1 (longer) or 2 (shorter) paragraph(s). Use a “Graff-like” template here, if that helps. Consult your summary analyses from your anthology. The following is a sample “big paper” Mrs. Ebarvia wrote a few years ago with herAP Lang students. In it, she questioned whether or not having more choices makes us happier. Her position is that more choices can be worse for us. Below is an excerpt from what she wrote: But does more choice—and the freedom to make so many choices—really make us happier? In “The Tyranny of Choice,” psychologist and Swarthmore professor Barry Schwartz argues that there exists an inverse relationship between the number of choices a person has when making a decision and his/her level of satisfaction with the final outcome of his decision. In other words, the more choices you have, the less likely you are to be happy with your choice. More specifically, in his research, Schwartz found that people could be classified into two different “decision-making” types: maximizers and satisficers. Maximizers, according to Schwartz, are individuals who tend to invest more time to product comparison and research before making a final decision. Maximizers “exert enormous effort reading labels, checking out consumer magazines, and trying new products.” On the other hand, when satisficers “find an item that meets their standards, they stop looking.” The result? Schwartz found that the greatest maximizers are the least happy with the fruits of their labors. When they compare themselves with others, they get little pleasure in finding out that they did better and substantial dissatisfaction from finding out they did worse. They are more prone to experiencing regret after a purchase, and if their acquisition disapoints them, their sense of well-being takes longer to recover. They also tend to brood or ruminate more than satisficers Rather than feel like their hard work pays off, maximizers continuously second-guess their efforts and furthermore, “[D]ecision-making becomes increasingly daunting as the number of choices rises,” and consequently, “more choice is not always better than less.” When maximizers are given more choices, they see not only increased risk in making the wrong choice, but see the choices they didn’t make as lost opportunities. This “opportunity cost” leads to overall dissatisfaction and regret; indeed, Schwartz argues that “[t]he consequences of unlimited choice may go beyond mild disappointment, to suffering” and even suggests that maximizers are more prone to depression. Schwartz believes we need to reconsider the value we place on unlimited choice and its effect on our overall levels of happiness. After you’ve finished summarizing your source and explaining the way it answers the question you initially posed, you should now add your own commentary on the source’s claims. What does this mean? It means explaining the extent to which the source is right/wrong or true/false based on your own experiences, observations, and readings. Do you agree or disagree with the source? Why? What personal experiences have you had that confirm or refute the source’s claims? Here’s an example I wrote (continued from above): As I considered Schwartz’s argument, I found myself identifying with the maximizers he described. I, too, tend to invest a substantial amount of time researching certain purchases. For example, when it was time to purchase a car seat for my first child, I not only reviewed official guides like the reputable Consumer Reports and surveyed all my friends who already had children, but I also read all the customer reviews on Amazon.com, BabiesRUs.com, and BuyBuyBaby.com. I started getting overwhelmed by reviews from users like “Concerned Father” who informed me that while the Britax Marathon car seat “shoulder straps are thick and wide” so they don’t tangle easily, the “side lock down mechanism is tightened more by the thickness of the belt [and] can pop open without much pressure” (No idea what that meant, but it didn’t sound good). Or from user “Justbooking,” who informed me that “the Roundabout is a better car seat for boys than the Marathon” (at the time, I didn’t know the sex of the baby, so this review had me panicked about gender-specific criteria, as if the “harnesses,” “tethers,” and “Latch-systems” of car seats weren’t enough to confuse me). On the other hand, user “M. Bostic” (finally, a real name!) claimed that the Britax Marathon was “a life-saver” and “it is quite expensive, but well worth it!” In the end, we did purchase the Britax Marathon after all. Having spent all that time researching and agonizing about my purchase, according to Schwartz, I should be less satisfied with my decision, perhaps even regretful. Yet, contrary to Schwartz’s findings, my car seat purchase is one that I feel fairly satisfied with. I feel no regret in making this purchase, even though the Marathon is one of the more expensive car seats on the market. If anything, the research I did only made me feel more confident with my decision. Despite some negative reviews, overall, the car seat consistently had the highest reviews. In fact, there really wasn’t a close second as far as a choice was concerned. The Britax Marathon was the clear winner. The research said so, and my experience with the car seat has only confirmed it. So is Schwartz wrong? Shouldn’t all the choices available to me have been a source of confusion and regret? Here’s the catch, though. In this case, there really wasn’t a “choice.” Because there was a general consensus about the quality of the product, the choice was easy. A no brainer. And because I’ve been pleased with the car seat’s performance, I’ve had no reason to be regretful. Well, what if I was disappointed with the car seat’s performance? Or what if the reviews and researchers weren’t in such broad agreeement? As the maximizer Schwartz described, I would most certainly experience buyer’s remorse, and the process of choosing a car seat would have been marked by anxiety, confusion, and self-doubt. In fact, the more I think about Schwartz’s central argument, the more I agree with him. Again, there really wasn’t a “choice” when it came to the car seat situation. But in cases where choice is abundant and a “clear winner” is not-so-clear, I am often dissatisfied with the results. When I go into a restaurant with many menu items that appeal to me, I have a difficult time choosing. Oftentimes, the moment I place my order, I have to fight the urge to tell the waiter I’ve changed my mind. If my meal isn’t satisfying—or even if it is—I’ll wonder if the other entree would have been better. (If someone at dinner orders the entree I wanted-but-didn’t-order, I may feel even more unhappy—I should’ve ordered that instead, I think to myself.) Although some may argue that having many entree choices offers customers an opportunity to “try something new,” I’d be interested to see how many people actually choose to do so. For example, according to their website, the Cheesecake Factory boasts a menu that “features more than 200 menu selections made fresh from scratch each day.” I have eaten several times at the Cheesecake Factory. Their menu is extensive and choices are limitless. Yet whenever I dine there, I almost always order the same thing—either the Thai Lettuce Wraps or the Shrimp and Bacon Club sandwich. I order these two dishes not because I even enjoy them that much, but because I enjoy them enough and I’d rather not take the risk in being disappointed with choosing something new. It’s a coping mechanism, I suppose, that I’ve come up with to manage all the choices available to me. It’s not about being happy with my choice; it’s about not being unhappy. As you can see in my example above, the first thing she did was explain how she identified with one of Schwartz’s claims (that she, too, is a “maximizer”). She gave an example using her car seat buying experience. However, her example actually disproved or refuted the source’s claims. She then gave another example, however, that supported the claims. You may find, like she did, that there are parts of a source that you agree with and other parts that you do not agree with. And that is okay. That’s what we call qualifying. STEP 3: Up Draft Now it’s time to build “up” your essay. Evaluate what you have written so far. Try putting things in some sort of tentative order. Then use one or more of the following strategies to continue your writing/thinking. (Note: the points below are not meant to be chronological “steps” to follow, but a list of suggestions. Each person’s process is different; use what works for you.)

My own models Over the past few years, I've been putting together a collection of essays about music. Two of them are featured on Medium.com--a great online site for publishing work and reaching an audience. They are both personal essays that explore an idea. They have much in common with your synthesis paper assignment and might serve as another model for your own. Here's one about the song "Auld Lang Syne" and another about "It's a Small World After All." Student Samples Check out these former student samples. In particular, notice how each writer begins the essay, integrates personal experience and expert opinion, organizes each section, and works in visuals as support.

Here are some from Mrs. Ebarvia's former classes: Your next blog should explore one or more the questions we discussed alongside "The Case Against High School Sports."

For this week's blog, choose a favorite quotation--something that inspires, validates, or challenges you. You should have a personal and positive connection with its meaning.

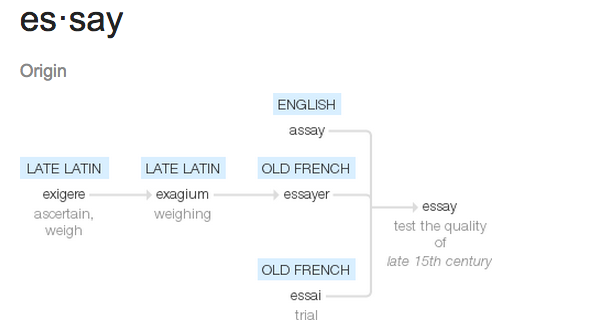

Search online to find a “notable quotable” that you agree with, that speaks to you. Here are some options for sources, but feel free to look around: Begin your post with the quotation. Be sure to attribute its author and/or context. For this week's challenge, use a CLASSICAL structure to organize your assessment of the quotation's significance. Due Friday am, as usual. Over the next month, you’ll research a topic of your choice. This topic may be broad or specific—regardless, you may find it helpful to think of your topic in terms of a central question (or questions) you want to pursue. What are you curious about? What have you noticed about the world around you? As Nancie Atwell asks, “What itch needs scratching?” What have you always wondered but never had the time or opportunity to pursue? Well, now is that opportunity. Eventually, this research will culminate into an essay, and by essay, I mean essay in its original, perhaps truest form. As you can see in its etymology, the word essay is about an attempt, a trial, a way to “test the quality of” some idea. With this in mind, an essay is less about proving something to be true, and more aboutweighing evidence and then exploring the ways in which something may be true. Your essay should be less about choosing a side and more about looking at a question from many sides. Consider this essay to be the culminating work of your year here in AP Lang. Let’s begin! Choose a topic Choose a topic or area of research that will sustain you over the course of the next few months. How to decide?

TOPIC SUBMISSION BY: MARCH 9th Research Anthology TYPES OF SOURCES

HOW TO FIND SOURCES Check out the following infographics to help with your Google searching:

And books! Consider using a chapter or excerpt from a book as one of your sources. Books sources, I’ve found, can be the most useful.

WHAT TO INCLUDE

Please Note: In lieu of a physical anthology, you may also create an online anthology using a webpage (such as your own WordPress site, using your existing WordPress login – go to WordPress.com to “create a website” – search YouTube for how-to videos), or an e-anthology (pdf) on USB drive, CD or DVD. See me if you have more questions. SAMPLES Here a few sample anthologies: Follow this link to look through some different print and web-based anthologies. Notice how many students used a Wordpress blog to create their anthologies.

NOTE: You must submit at least one source for your anthology by Wednesday, March 16th, for a grade and to ensure some feedback. Include all required components to your sample as outlined above (introduction, article, then summary, with MLA citation at end). Then after the sample is assessed and returned, include it—with any needed revisions—with your completed anthology. The Essay More details about your essay will follow, but here are the basics: 2000-ish words, formatted in “magazine” style. Minimum five sources cited, including at least one primary source interview. (What a sneak peak at the kinds of papers you'll be writing? Check out these former student samples. In particular, notice how each writer begins the essay, integrates personal experience and expert opinion, organizes each section, and works in visuals as support.)

The Talk After you complete your final essay, you’ll present your work to the class in a brief talk to the class, approximately 7-8 minutes in length. More details to follow. THIS WEEK:

PART ONE: READING So far, you’ve read four personal history essays: “A Primer on the Punctuation of Heart Disease,” “The Chase,” "Difficult Girl," chapter 1 of Teacher Man, and an excerpt from Mindy Kaling's memoir. David Sedaris' "Me Talk Pretty" was a good example from earlier in the year. Below is a list of some other personal history essays that might serve as inspiration. You are required to read at least TWO additional essays from the list (or New Yorker link) below. Your choice. I will be asking you to respond to TWO of the essays later in the week, so select two that you'd like to respond to--one you've already read or one you'll read this week. (More on that later.) Read at least TWO of the following essays.

Each essay offers something different in terms of personal history. No matter which essay you choose to read—together or on your own—pay attention to the qualities of effective writing that each essay possesses. Notice the specific ways in which each writer approaches the Six Traits. How do they present their ideas? What types of content are included? How are the essays organized? How do the ideas unfold and why? Why this anecdote at this particular moment in the essay? How does the writer’s voice come through? How are the writer’s “fingerprints” all over this essay? How does the writer clarify ideas with specific choices in words? How do the sentences enliven the writer’s ideas? What does the essay sound like? Can you comment on its pacing? Its tone? PART TWO: WRITING Begin the drafting process: brainstorm, use your writer's notebook, get a document going, etc. In writing our personal history essays this week, we’ll use the definition that the New Yorker uses: Writers reflect on the intimate events and memories that shaped their lives. With this in mind, some guidelines:

Stuck on what to write about. Check out this handout of suggested approaches to Personal Histories. For the rest of the year, we’ll be taking some of our writing into the online world through blogging! Blogging will be your opportunity to share your thoughts and ideas with each other outside of class. As an added benefit, blogging will also give you the opportunity to improve your writing (and thinking) skills. Even though you’ve heard the word blog before, here’s a great 3-minute overview from Common Craft videos: Before you can begin blogging, you’ll need to sign up for our blogsite, which will be housed on WordPress at aplangandcompsmith1516.wordpress.com You can also find the link to your blogsite anytime by using the dropdown menu above. FIRST, you will need a WordPress username. To get a WordPress username, click here to sign up. Once you have done that, you will receive a confirmation email. Be sure to activate your account. SECOND, send me your username by filling out this form. I will invite you to our blogsite using the information you provide. THIRD, check your email for your invitation to our blogsite. Accept the invitation. When you click “accept,” you may receive another invitation that says something to the effect of “You’ve been added!” with a “view blog” link. IMPORTANT: You can’t get started until you receive an e-mail invitation from me. If you do not get an e-mail invitation, let me know. FOURTH, now that you’ve been added to the site, learn how to log in and take a quick tour with the video below. Just note that I made this video for last year’s students, so some things may be slightly different, but essentially it’s all the same. :) Here's a list of suggestions for studying for the AP Lang midterm:

Choose a significant passage from the novel and write a rhetorical analysis.

FIRST, choose a passage. When choosing a passage, consider the following:

THIRD, begin drafting/writing/revising your rhetorical analysis. Your final rhetorical analysis essay should be about two pages in length (between 400-600ish words). Some tips:

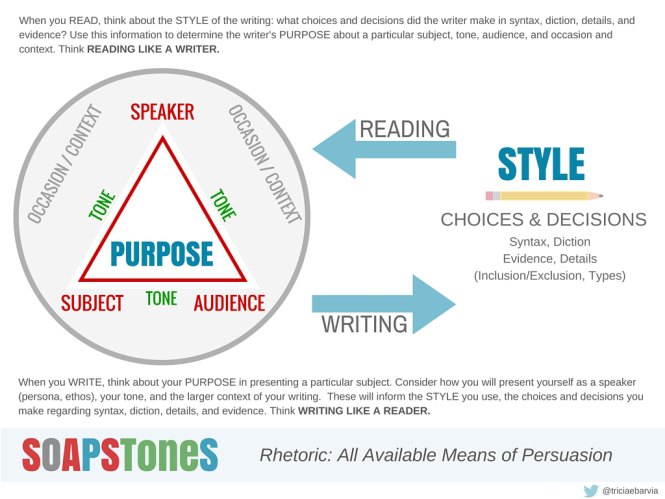

In “How to Read Like a Writer,” Mike Bunn points out that when you read like a writer, “you examine the things you read, looking at the writerly techniques in the text in order to decide if you might want to adopt similar (or the same) techniques in your writing” (72).

Let’s look at Tim O’Brien’s story, “The Things They Carried,” as inspiration for our own writing. To that end, think about the techniques O’Brien uses in that particular short story to convey the various things that the soldiers carry. Also keep in mind the diverse types of things the soldiers carry: individual/group, objective/subjective, concrete/abstract, mundane/extraordinary. Using “The Things They Carried” as your model, write-like Tim O’Brien. In a “write-alike,” you will borrow O’Brien’s diction (though not his specific words) and syntax. Try to mimic O’Brien’s style. However, instead of writing about what soldiers carry, you will write about a subject a little closer to your own experience―being a student. Write-like O’Brien for about 250-300ish words. Use the “backpack” activity from class to help you compose your piece. ALTERNATIVE: As I mentioned in class, if you would like to “play” with this assignment a bit more and use a different group of people (for example, artists) and a different verb than carry (for example, draw), feel free to take the weekend to work on this exercise. TYPED, DOUBLE-SPACED, MLA HDG. DUE TUES., 1/5/2015. After the class discussion takes place, you’ll reflect on how the discussion went from your point-of-view, whether you were in the circle or out.

Type a one-page reflection that answers the questions below. Please answer in a brief paragraph for each, labeling each response by the corresponding number. You may single-space your response (with a double-space between each question).

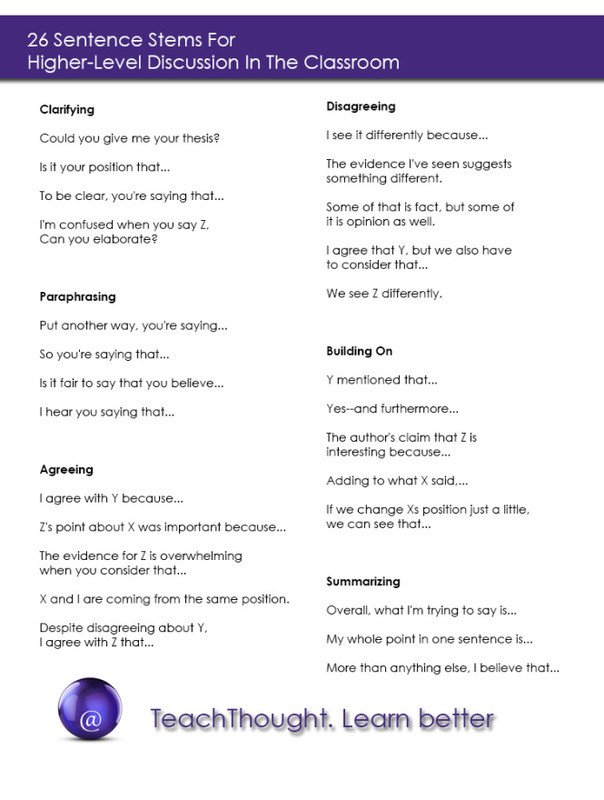

Participating in an active discussion—especially with the eyes and ears of your peers around you—can be an intimidating prospect. Remember that effective discussion requires both talking and listening. As a friendly reminder, some etiquette tips for discussion are provided to the right. When you are in the inner circle, consider using the following stems, which can help move discussion in positive, productive directions. If you are in the outside circle, participate as if you were in the inner circle, just without talking. For example, if the inner circle is looking at a passage, open your book to the same passage and follow along. In addition, take notes on how the discussion is going: how is the discussion progressing, what points stand out to you, which points are developed/not developed, etc. Take active notes; you will need these to complete your reflection that night.

BYOD Tech Option! If you have a question for the inner circle about the content of their discussion, pose your question on the “backchannel” provided via Socrative.com to have your question addressed by the group. 1. Go to Socrative.com. 2. Click on Student Login. 3. Enter ------------- as the classroom ID. 4. Post your question. As part of our discussion of O’Brien’s novel, we will zoom in on three short stories as well as the take a “whole view” analysis of the novel. Each student will sign up (or be assigned) a short story discussion group. On your discussion day, you’ll gather (for the first time) as a group to discuss the story while the rest of the class listens, observes, and takes notes.

To prepare for your discussion, review your short story in greater detail. Consider this your “second draft” reading. As you reread the story, think about what you see now that you didn’t see before (eye doctor analogy). Specifically, come to class on your discussion day with notes on the following (they will be extremely helpful during discussion):

After each discussion day, you must turn in a reflection and notes on the discussion (see Part 2 above). A novel!

You’ll need a few things for your reading of Tim O’Brien’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Things They Carried. Be sure you have the following supplies each day in class:

Take notes on a minimum of six passages that stand out to you for their descriptions of people, places, or things. Remember that “things” can be concrete (the soil or land) as well as abstract (shame or love). Make sure you choose passages that span the breadth of the novel (i.e. do not choose six passages from the same chapters). You may choose any combination of descriptions―3 places, 2 people, 1 thing or 4 things, 1 place, 1 person―as long as you have one of each. You may find yourself wanting to note more than six descriptions (that’s how good O’Brien’s writing is). Feel free; six is only a minimum. Choose six meaningful passages. Think about that word―meaningful. The passage should be full of meaning. Note the passage by marking it in the book with the post-it note. On the post-it, answer / reflect on the following for each passage:

Be prepared to discuss “fishbowl” style or in Socratic circles. Your notes will be extremely helpful. In addition, you will be given a multiple choice quiz to verify you’ve read the novel. If you read diligently and carefully, you should be fine. * You may find it helpful to mark the passages first and then write responses later. That way, you can just enjoy the novel and then go back to write on the post-its now that you have a “bigger picture” view of the novel upon finishing. To appreciate great personal writing, we will read a collection of essays from many great writers. These "On Essays" focus on a single aspect, issue, or activity of the writer's life and experiences. Writing in a variety of modes, they succeed because they explore complex topics in a very relatable way. They explain, define, and describe; they use anecdotes and allusions. They feature both insight and curiosity. They zoom in and zoom out.

Clicking here will take you to a folder of "On essays," most of which we will read in class. They will act as out mentor texts. Read them carefully, reflect on our conversations, and revisit your annotations. You will write at least 2 of these essays in the first semester. Start thinking of possible topics for your own essay. Use your notebook. Do lots of pre-writing before you jump in. What do you need to explain to your reader? What descriptions would be interesting and valuable? What ideas or terms need definition? What comparisons or references could you make to connect with your reader? Where could you slow time? Where should you speed it up? Yes, it's a lot to think about--which is why we will do at least 2 drafts for each essay. You will have the opportunity to meet in small reading groups that will act as a writers' workshop. Keep this in mind when you compose your essay. You will be reading them to a group of 2-3 students for immediate feedback. The requirements:

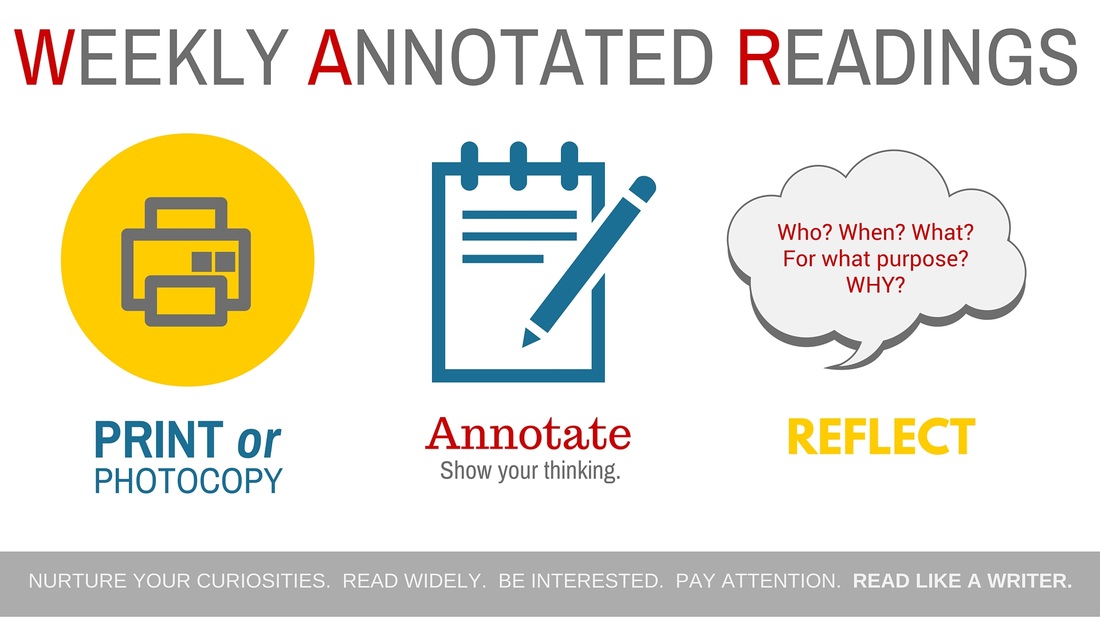

I will use a modified 9-point AP rubric, available here. They will be worth 50 points. Questions or concerns, come talk to me.  Reading is an important component to any writing class. You will be required to submit evidence of brief, weekly independent reading. Since this reading is independent, the choice of topic is yours. Read widely to explore a range of topics. The goal of this assignment is to become exposed to as much high quality longform essay writing as possible. Read in a variety of publications or examine the writing styles of a single publication. Read one writer or a different writer each week. Note that the culminating project of this course is a research essay on a topic of your choice; use your weekly independent reading as a way to explore topics that interest you. Expect to share what you have read with the class. GUIDELINES Find a piece of writing from a respected publication from the list below. Find feature-length,longform essays. These are generally longer articles or journalistic works (1000+ words), often originally published in the print edition of the magazine and then republished digitally. No blog posts (if you are unsure about what a “blog” post looks like, ask first). If a publication has a “magazine” tab, look there. Better yet, check out the great magazine display in the library (which is conveniently located next to the copy machine!).

Turn in your weekly reading every Monday. First annotated reading is DUE MONDAY, 10/12/15. RECOMMENDED, APPROVED SOURCES The following publications should provide you with plenty of interesting articles and essays to read. If you find a compelling article from an alternate publication, run it by me first. For your convenience, hyperlinks provided below.

Note: If you hit a paywall while looking at articles, take note of the title, author, and publication. Then search using the Stoga databases (try Ebsco or ProQuest). Chances are, you’ll be able to retrieve the article through the school’s subscriptions. Word Journal

What is your relationship with language and words? This project asks each student to consider his or her personal relationship with words. You will create a journal of words from a number of different categories listed below. 1. your first word 2. your top ten favorite words 3. your top five least favorite words 4. a word that has gotten you into trouble 5. a word that is often used to describe you 6. one of your relative’s favorite words 7. one of your friend’s favorite words 8. a slang or made-up word you like to use 9. a word you learned in the past year 10. an original collective noun of your own* 11. an original word for a thing/idea/concept, etc. that has no English word *more on this topic later Your book of words should have a creative cover and be visually appealing. The pages inside should be thoughtfully designed—use pictures or drawings, etc. Each section should be labeled according to the categories above. Please cite any sources consulted. You are required to have fun creating this project. The book is due Thursday, 9/24. Get a Writer's Notebook!

You will need a writer’s notebook. We will use it every day—to write, list, plan, brainstorm, draw, map, ponder, practice, model, plot, compose, revise, and make wild, impossible plans. It is YOUR property. I don’t want to read it—unless you feel like sharing—or collect it. It just needs to be with you at all times. It’s where all your work will start. It will need lined paper--at least on one side--but it can be any size, any shape, any color. You can get a fancy one with a kitty cat or a crazy pattern or use a simple, spiral notebook. Your choice. It just needs to be bound--as in not loose leaf paper. DUE: first week of school. An Essay of Introduction

Welcome, AP Lang’ers! The success of our year together will depend partly on how well we get to know each other. So for your first assignment, you’ll write a brief essay that introduces yourself to me and to your classmates, which you will read aloud during class. Some guidelines:

I’m looking forward to getting to know you and hearing your essays! |

Archives

June 2016

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed